News & Insights | 3rd June 2021

Investment Management

20 Min Read

Cryptocurrencies are enjoying their latest moment in the spotlight, not just amongst the investment community, but the world at large. Everyone has a strong opinion: which to invest in, or whether to invest in them at all. But how much do you know about cryptocurrencies?

Our latest paper takes a deep dive into cryptocurrencies covering topics such as: how does crypto work, what are distributed ledgers and blockchain security, and is cryptocurrency technology as disruptive as it is currently perceived?

It also looks at the sustainability of crypto mining, the logistical suitability of using Bitcoin as a currency and its long-term influence on investment.

Most of us have overheard numerous conversations drifting across pub gardens and outdoor dining areas about cryptocurrencies. Much like the other staples, politics and Covid, everyone seems to have a strong opinion: which to invest in, or whether to invest in them at all. We have all heard proud boasts of eye-watering returns, and equally lamentable losses. Understandably, clients have been asking our views as reports emerge of institutional investors starting to dip their toes into this nascent asset class.

There are so many questions to answer. What is a cryptocurrency? How are distributed ledgers and blockchains related? Who are the miners? Is it purely the realm of nefarious individuals or can investment be legitimate? Is it a flash in the pan or is it the advent of a brand-new technology that will disrupt finance? We will attempt to answer these and other questions below, starting with a brief introduction to the technology that is the basis of so much pontification.

So how does a cryptocurrency transaction differ from a traditional one?

When you make a purchase for an item at a store, the typical process is as follows:

This process is only as secure as either of the two banks’ security systems protecting their centralised record of the balances of all their clients’ accounts.

In the “crypto” world this process is handled differently. There is no banking system; instead, everyone has their own digital wallet containing a history of every transaction that has ever occurred and the current balance of every other digital wallet. Since every user (or node) of the system has this record, it is called the “distributed ledger”, there being no bank in the middle of it all.

When a transfer is requested from one wallet to another, the following happens:

Originally starting out as individuals in the network using their home computers to solve the cryptographic puzzle and verify the network’s transactions for a small prize, mining has now become big business. Specialist mining rigs involving tens of graphics processing units (GPUs) chained together and dedicated server farms have sprung up as the rewards for mining have been going up in line with cryptocurrency prices. For example, this prize for the largest cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, is 6.25 BTC with a value of around $393,750 at end of May prices.

You would be forgiven for thinking this is overly complex, it appears so on the surface, but what it results in is an exceptionally secure system, more so than the traditional banking process outlined first. Having a distributed ledger means that it is much harder to hack the system. The moment an attempt was made to change a ledger, it would instantly be at odds with every other ledger, recognised as being erroneous and therefore rejected.

The cryptographic puzzle is important to ensure that the latest additions to the ledger are also secure. It can only be solved through trial and error. This means that the first miner to solve the problem and therefore submit the latest block to the chain, is not predictable, it is determined by chance. This makes cheating hard as a cheater can never know when they might have the opportunity to cheat. Having other miners check your work also reduces the scope for deceit.

This technology can be extremely powerful. If you know there is a 100% secure way of transferring ownership of an asset, validated not by just one counterparty but thousands and thousands, you can get excited by a host of possible applications. For example, imagine you live in a country where you worry about state and business corruption, and you wish to purchase a house. Imagine ownership of every house was represented within a distributed ledger and managed by a blockchain. You would no longer have to rely on a series of banks or the government land registry to formally transfer ownership of the property. No one in the future could dispute a transfer and lay claim to your house, the purchase would be stored in not just your ledger, but the ledgers of thousands and thousands of other homeowners who could all verify you did indeed own it. Furthermore, if you can be confident in the authenticity of every stage of the process, you can fully automate it. No more would you have to chase up solicitors for procedural paperwork, but rather it could automatically be completed and sent to the counterparty on successful completion of each stage of the transaction, a feature referred to as “smart contracts”.

This is just one of many applications that entrepreneurs are trialling as they get to grips with what this technology could do. Like many early-stage innovations, the major use may not even be in development yet. However, for all the benefits that we have listed above, there are some notable trade-offs with the technology and more importantly the investment case for them.

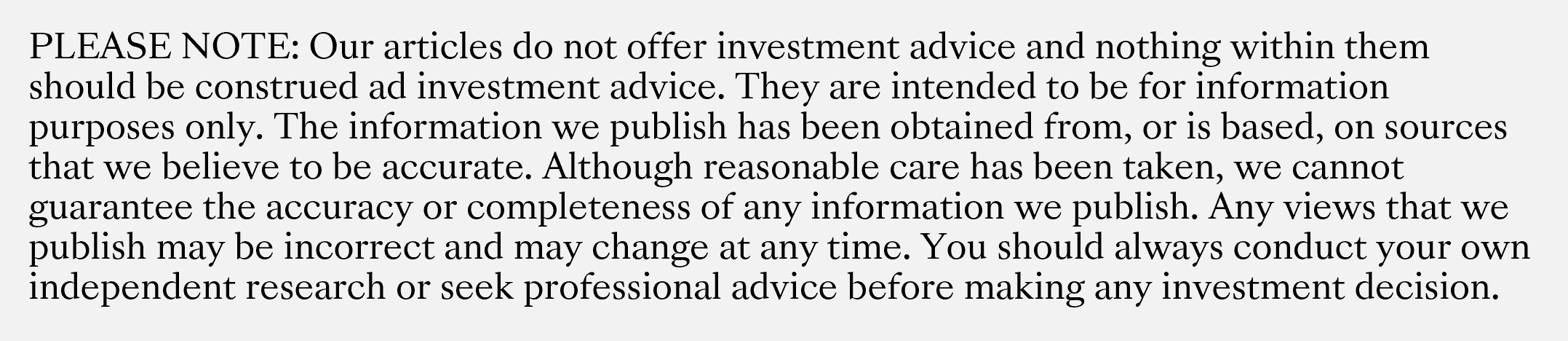

We have been commenting to our clients this year that mining of the most popular and largest example of a cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, consumes more energy per year than a small country. It has now overtaken a number of larger countries, including the Netherlands, Finland and Belgium. As the value of Bitcoin increases, so do the number of miners trying to solve the cryptographic puzzle, increasing the amount of energy consumption. At its peak this year, Bitcoin mining energy consumption had overtaken Sweden on the below graph.

[1]

This is one of the major costs to this technology. The security that the distributed ledger and the cryptographic puzzle grants comes at the cost of a huge amount of computing power. In Bitcoin’s case, the difficulty of the puzzle is regularly stepped up to ensure it always takes around 10 minutes to solve, offsetting any increase in computational power that newer computers provide. We are in a position where faster and faster computers are constantly needed to trawl through more and more possible solutions for a problem that is getting harder and harder to solve. This makes energy the key cost for miners and 65% [2]of the world’s mining is conducted in China where energy is cheapest. Unfortunately, this is also some of the “dirtiest” energy on the planet, with most of it supplied by coal fired power stations. Proponents of cryptocurrencies note that the world will soon move to being predominantly renewably powered, but this misses a key point. It is not currently, and this sort of activity is providing huge demand for coal fired energy infrastructure making it harder to decommission.

It is worth noting that there are some solutions in the works to attempt to offset this issue. The main one being developed replaces the cryptographic puzzle (referred to as “proof of work”) with something called “proof of stake”, where every node in the system puts a proportion of their own money into a communal pot that would be forfeit should there be any instance of foul play discovered. Others include pairing down the “proof of work” to take less time and require less computational power to solve.

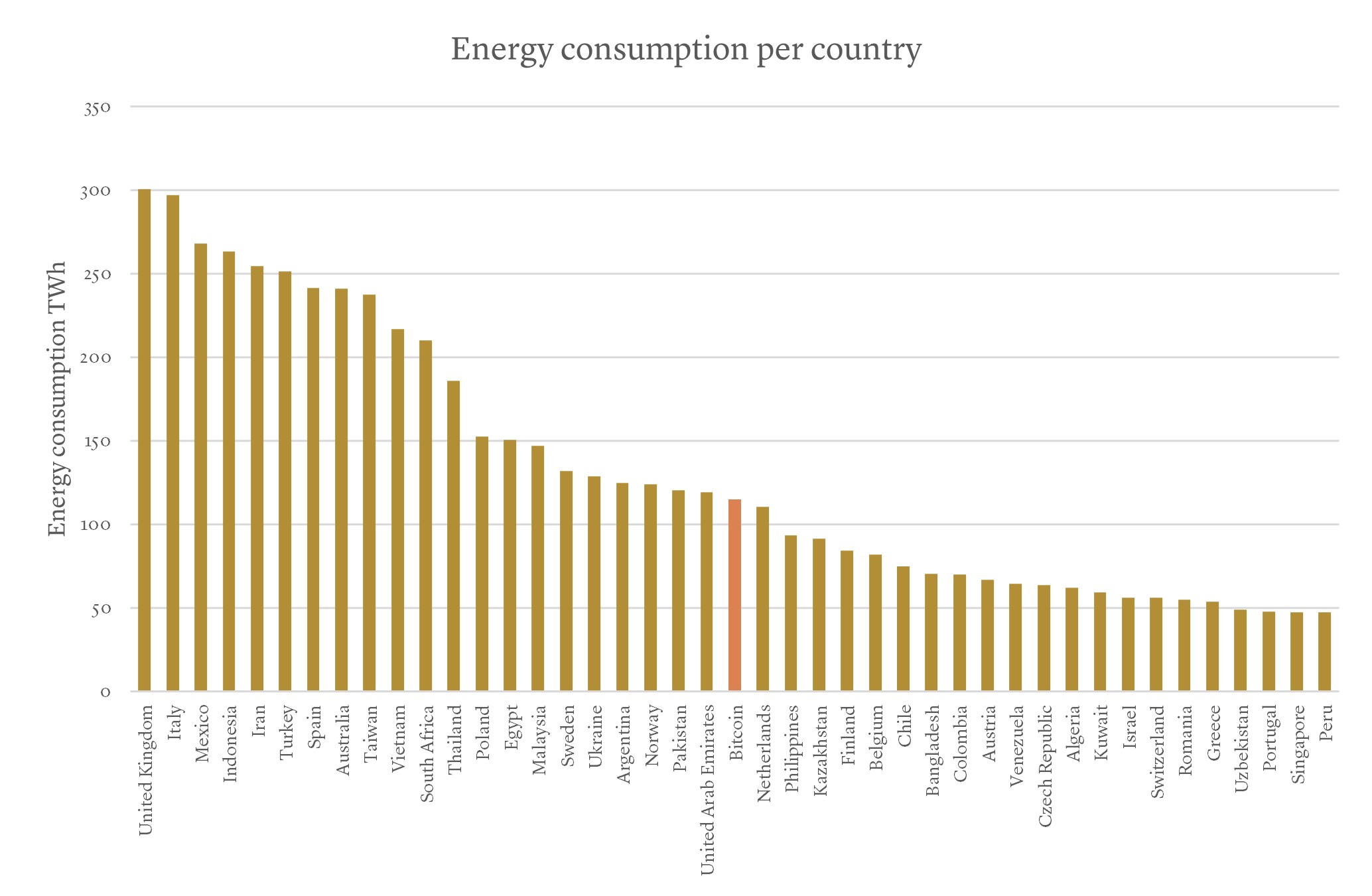

Another limitation is just how many transactions can be processed given the need for a 10 minute “proof of work” prior to adding the latest block to the chain. By way of comparison, the VISA network that so many of us have come to rely on processes roughly 25,000 transactions a second. Bitcoin by comparison struggles to process five [3]. Given each block of transactions requires a reward to the miner that solves the cryptographic puzzle, the cost per transaction is also high. An outstanding question remains whether users are prepared to pay the additional cost in exchange for greater security or arguably anonymity.

[4]

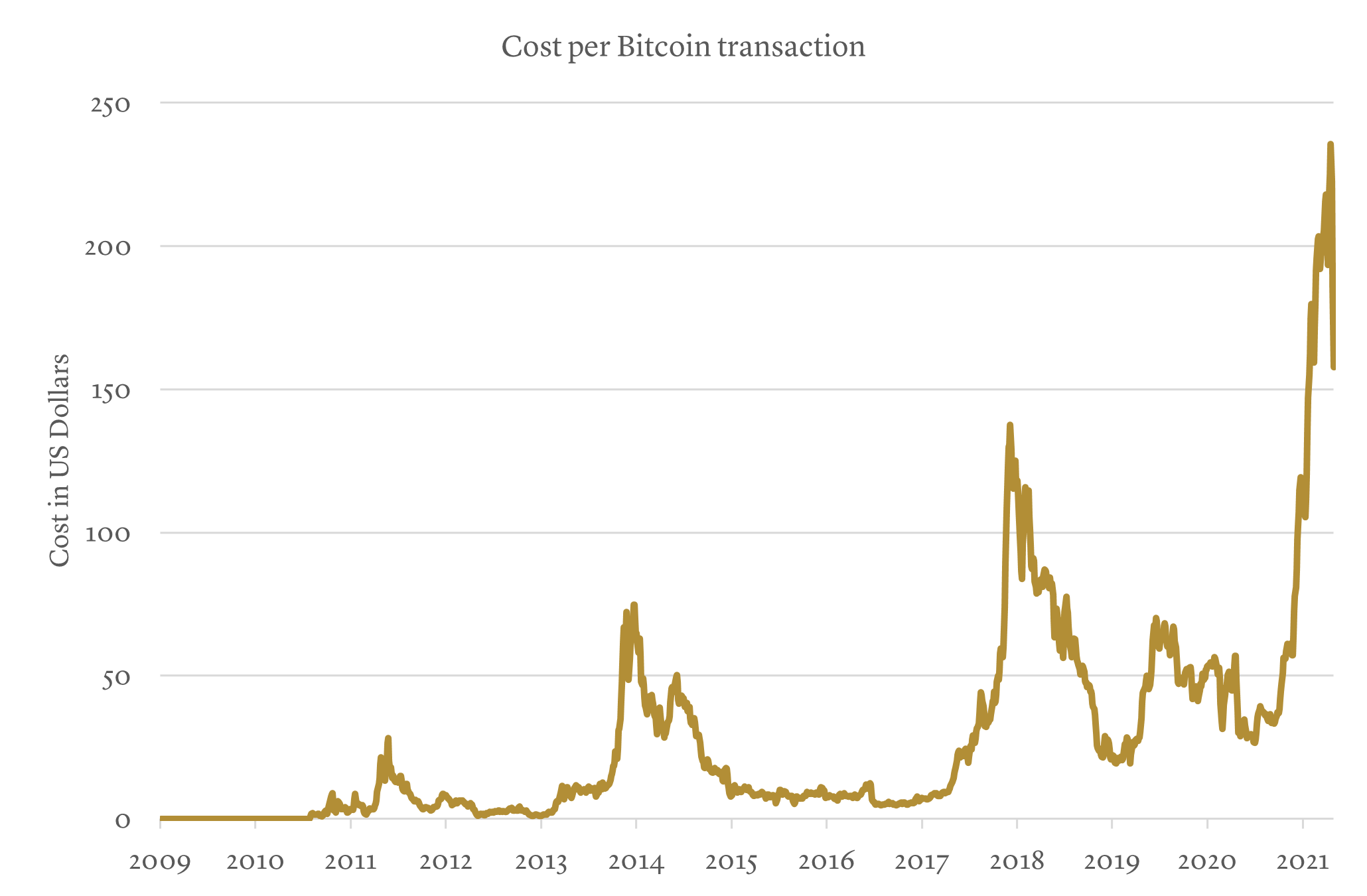

One of the interesting facets of Bitcoin is that the system is set up to ensure that only 21m bitcoin are ever created. Its supply is hard coded to be finite. Proponents often hold this up as a significant benefit in a world where largescale money printing has the potential to debase its value. Extreme examples of this historically have been hyperinflation in Weimar Germany and more recently in Zimbabwe, where the value of the Zimbabwean Dollar fell so much that eventually the printing of a one hundred trillion-dollar note was necessary.

Limiting the ability for governments and central banks to do this might seem beneficial. However, we used to have a system much like the one crypto evangelists espouse. Gold and precious metals were used as a medium of exchange on account of their scarcity, lustre, chemical inertness, and gratifying weight. Eventually, this evolved to goldsmiths providing paper receipts for deposits of gold, which were then used in commercial transactions to avoid needing to continually withdraw and deposit the physical underlying asset. Paper money backed by physical gold was born. This evolved over time into central banks being the institutions issuing currency backed by gold reserves, which persevered through the Gold Standard and Breton Woods eras and ended abruptly in 1971. This was dubbed the “Nixon Shock” as the President stopped the direct convertibility of dollars into gold, in response to growing economic pressures, without notifying the IMF or the State Department. The issue with this historic system was that it resulted in more significant and frequent banking crises [5] as liquidity (cash) could not easily be injected into the system if economic fears incited mass withdrawals from the financial service sector. The move to “fiat” money, where currency does not need to be backed by anything other than the belief of value and government control, has introduced a greater set of policy tools, dubbed monetary policy. These help smooth out economic cycles, although the key is that these powers are used responsibly. However, using a finite supply cryptocurrency instead of modern-day fiat money would remove these policy tools and the corresponding economic management benefits they have been shown to have.

At the moment, digital wallets are pseudonymous. It is essentially a public 256 bit key (the address of the wallet) protected by a private 64 character key (or password to the wallet). There is no other identifying factor. Lose or forget the private key and you lose access to all the contents of the wallet with no hope of recovery. Unfortunately, this happens too frequently with an estimated 20% [6] of all Bitcoin in digital wallets that are no longer accessible. For regulators this poses a problem. How can you determine source of funds and their legitimacy? How do you protect retail investors against co-ordinated market manipulation in the way you do in stock markets? Janet Yellen, the former chair of the Federal Reserve and now the Treasury Secretary for the Biden administration voiced fears about the uses of cryptocurrencies: “To the extent it is used I fear it’s often for illicit finance.”[7]

The counter to this is that physical cash is still the predominant form of currency used in illicit transactions, however Yellen’s comments serve as a useful warning that regulation of this space is coming. This could dent the attractiveness of cryptocurrencies as it adds frictional costs for users and institutions who have to both comply and demonstrate that compliance to the regulator. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has already banned the investment in cryptocurrency derivatives and exchange traded products for retail clients [8] and China has banned all cryptocurrency trading. Whilst the latter might be due to that authoritarian regime’s desire for control over all elements of their financial system, the former is driven by genuine worries about the risks retail investors are taking without regulation in place for their protection.

Overall, Bitcoin is rather easy to discredit as being a currency, which is traditionally described as having three characteristics: a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. It is not a medium of exchange, very few institutions accept Bitcoin as a method of payment. Even the renowned Elon Musk reversed his recent policy of having Tesla accept payments in Bitcoin. It is not a unit of account, the value of Bitcoin has oscillated too wildly for anyone to truly measure their worth, salary or other economic facet in Bitcoin. The last test, whether it is a store of value is still to be seen, but this is where the strongest arguments for it lie.

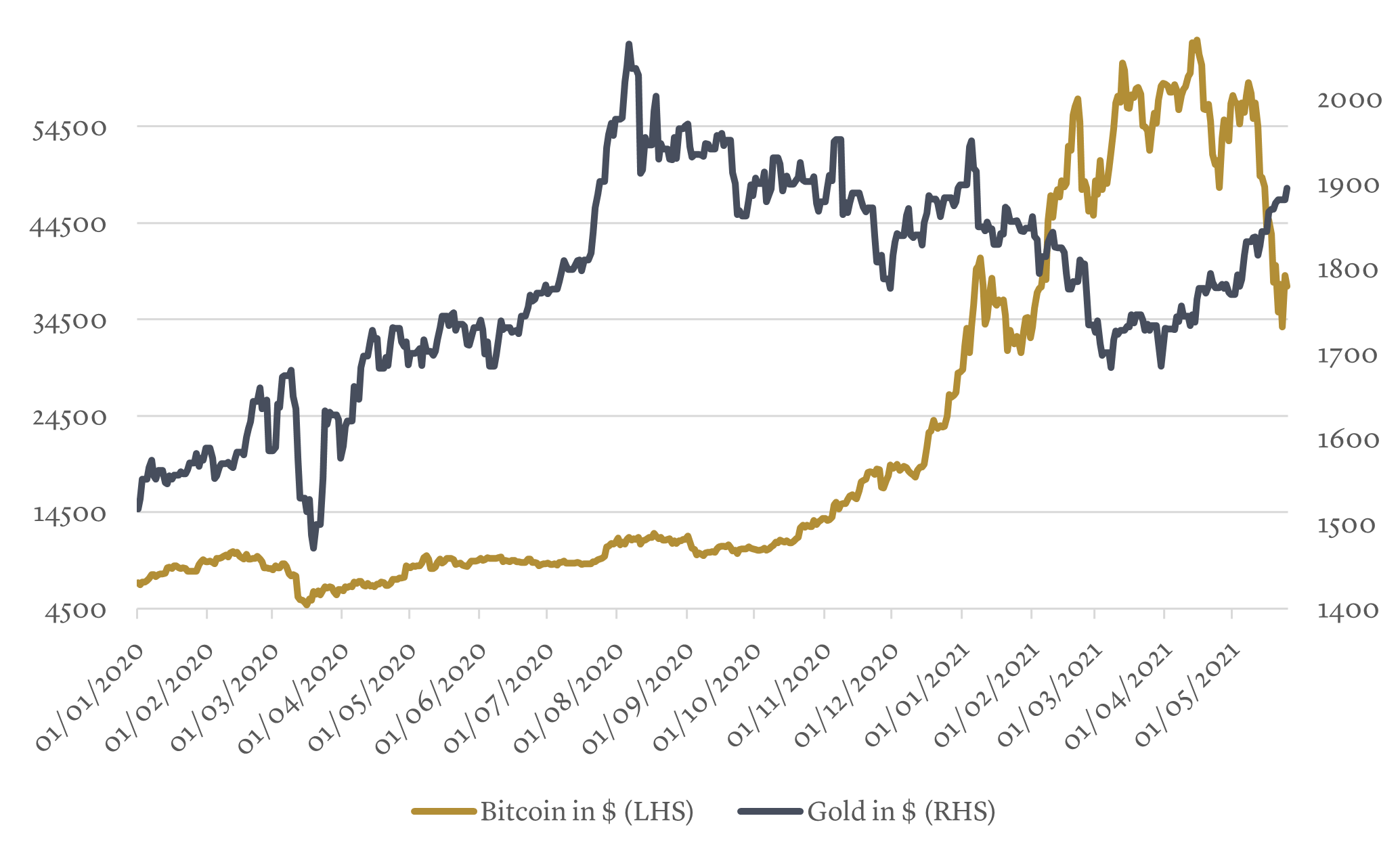

Gold has always been the insurance policy against the devaluation of traditional currencies, inflation and a safe haven when the world’s financial systems are under stress. This characteristic has helped keep the price of an ounce of gold higher than other precious metals when adjusting for scarcity. It is embedded in our consciousness that Gold is the ultimate store of value that keeps track with inflation over the longer term. There is possibly no better example than an ounce of gold buying roughly the same amount of bread in King Nebuchadnezzar’s time (562 B.C.) as today [9], or the wage of a Roman centurion (27 B.C. to 13 A.D.) paid in gold, being roughly the same as that of an experienced captain in the British Army today. [10] Rather than being a digital currency, could Bitcoin instead be digital gold? It has the same finite supply that gold has. Its security is a huge bonus, and whilst there are transactions costs and speed constraints for trying to use Bitcoin as a currency, it is clearly more portable than trying to trade, deliver and store physical gold, although both require energy to mine. The problems with this argument are twofold. One, it has not got the same history of fulfilling this role in our society as gold does. Second, it has not behaved like physical gold since inception. It has behaved much more akin to the riskiest investments than the safest. As you can see in the below graph, the two move in opposite directions to each other.

[11]

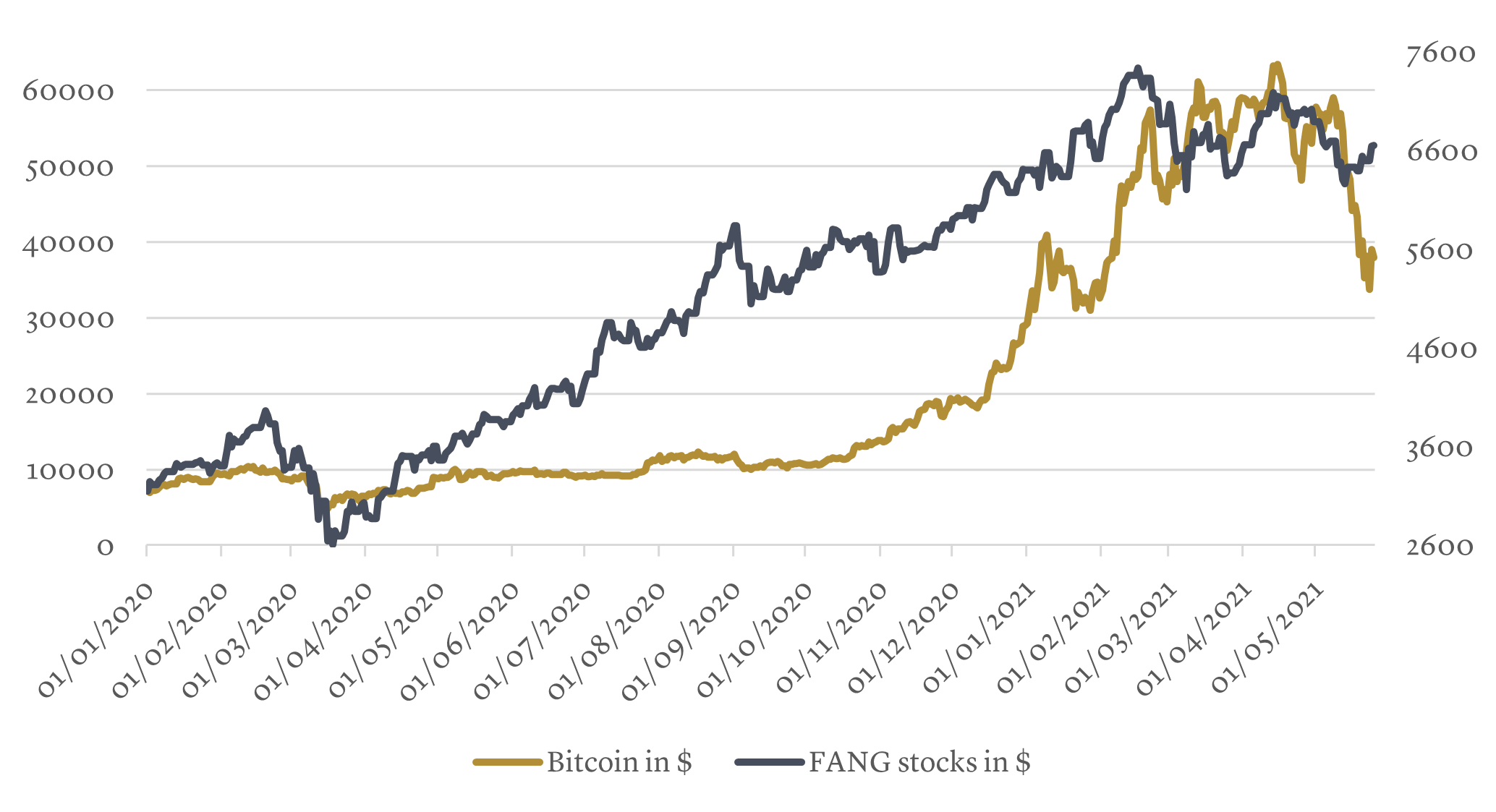

You can see that its price was far more akin to high growth technology businesses, as shown by the performance of the “FANG” stocks (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Google) below.

[12]

We are still open to the thesis that Bitcoin might evolve into being digital gold down the line. Gold has a market size of around $15 trillion and if Bitcoin could start to take some of this market share, then at least you have a framework to value it. For example, should it be able to justify a 15% share of the “anti-fiat hedge” market (or in plain English, insurance against cash being devalued through excessive printing), then you could calculate a Bitcoin to be worth $120,000. That is a big if.

In the meantime, it appears people in the western world have been spending their higher-than-normal savings accumulated during lockdown on cryptocurrencies. Their thesis? “It’s going to the moon.” We are very wary where the sole reason for investment is thinking that the price is going higher, with no way of justifying that higher price. The ascent of “Dogecoin” which started out as a joke, is a perfect encapsulation of how rampant this sort of speculation became. Matt Levine, a columnist for Bloomberg has perhaps captured this best:

“Just imagine traveling 10 years back in time and trying to explain this to someone; just imagine what an idiot you’d feel like. “There’s going to be this online currency that people think is a form of digital gold, and then there’s going to be a different online currency that is a parody of the first one based on a meme about a talking Shiba Inu, and that one will have a market capitalization bigger than 80% of the companies in the S&P 500, and its value will fluctuate based on things like who is hosting ‘Saturday Night Live’ and whether people tweet a hashtag about it on the pot-joke holiday, and Bloomberg will write articles and banks will write research notes about those sorts of catalysts, and it will remain a perfectly ridiculous content-free parody even as people properly take it completely seriously because there are billions of dollars at stake.” [13]

All things considered the underlying technological innovation that is the foundation of all these cryptocurrencies is exciting. Whilst there are pros and cons, the other question we must ask ourselves is not just whether the technology will succeed and become wider spread, but also, will investments into that technology be profitable? Looking back to the end of last century, the advent of the internet was a significant technological innovation. Expectations of how much it would impact every facet of life were probably understated if anything. Stock prices skyrocketed as investors piled money into anything internet related. It is worth reminding ourselves of some of the darlings of that periods: Boo.com, Pets.com, AOL, Netscape, Yahoo, Lycos, Alta Vista. For every Amazon there were three of four other businesses that no longer operate today. As it stands, there are around 1,700 cryptocurrencies with a market value of over $1 million [14]. The greater the number, the lower the chance you pick the handful that will end up both changing the world and being successful investments.

We have espoused this view as the price of Bitcoin was surging up to its high of over $63,000 per bitcoin in mid-April and whilst the price fell swiftly to a recent low of under $34,000 at the end of May. As ever, we will continue to track the progress of innovation in this space and will revisit the investment case frequently. At the moment, we believe too much speculative investment has swamped the true value that some of these investments might have and with so many cryptocurrencies being launched, it is hard to identify the longer-term eventual winners. This increases the risk of large falls, such as we have seen with Bitcoin, which has dropped by more than 80% on three separate occasions since inception. We would not want to endanger the careful financial plans we have in place for our clients at this junction. However, as with so much of our investment process, if the data changes, so will our view. We will keep you posted.

[1] US EIA and Cambridge centre for alternative finance. Note: Electricity consumption values are based on the most recent available year (2018 or 2019)

[2] University of Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (https://cbeci.org/mining_map)

[3] and [4] Blockchain.info

[5] Elmus Wicker, Banking Panics of the Gilded Age (2006) and Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Roggoff, This time is different: Eight centuries of financial folly (2009)

[6] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/13/business/tens-of-billions-worth-of-bitcoin-have-been-locked-by-people-who-forgot-their-key.html

[7] https://markets.businessinsider.com/currencies/news/janet-yellen-bitcoin-is-an-extremely-inefficient-way-to-transact-2021-2-1030109052

[8] https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/fca-bans-sale-crypto-derivatives-retail-consumers

[9] https://capital.com/gold-price-forecast-next-5-years

[10] https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/news/2021/01/21/gold-and-inflation/

[11] Bloomberg, BTC USD cross and Gold Spot price – 01/01/2020 until 25/05/2020

[12] Bloomberg, BTC USD Cross and Equal Weighted FANG Index Total Return – 01/01/2020 until 25/05/2020

[13] https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-05-06/dogecoin-is-up-because-it-s-funny

[14] https://coinmarketcap.com/all/views/all/